Milk fever in cows is one of the most common conditions in the dairy industry.

Indeed, it is a significant macro mineral disorder which affects transitioning dairy cows.

The main causes of this condition, and the various treatment options and prevention methods have evolved over the years.

They are considerably well accepted and adopted by veterinary surgeons.

Let us delve deeper into understanding what milk fever is, as well as discuss the main causes and symptoms, along with management and treatment.

Article Chapters

What is Milk Fever in Cows?

Milk fever, or hypocalcaemia, is a metabolic disorder which is caused as a result of insufficient calcium.

Cows suffering from milk fever will thus have lower levels of blood calcium.

This condition generally presents itself within the first 24 hours post-calving.

In some cases it could also occur up to three days post-calving too.

Calcium plays a key role in muscle function as well as a cow’s immune system.

So if blood calcium levels are too low, it will not be enough to support nerve cell function or the contractions of muscle tissue.

What Causes Milk Fever

Image source: Shutterstock

Milk fever may be clinical or subclinical.

In clinical cases cows (both downer as well as non-downer) will have less than 1.4mM of blood calcium.

In the case of subclinical milk fever, blood calcium will be in the range of 1.4mM and 2.0mM.

As a general rule, it is recommended that blood calcium levels are monitored before calving.

It is important to stimulate an increase in calcium absorption levels using a suitable diet throughout the pre-calving period.

Indeed, some degree of hypocalcaemia occurs in all cows during calving.

However, clinical signs tend to develop once the condition is quite severe.

Cows have approximately 10g of calcium circulating in their blood.

However, they have a significant amount of calcium in their bones (around 6000g), and around 100g in food in the gut.

During the late stages of pregnancy, and during early lactation, the demand for calcium increases considerably, and this leads to the blood calcium levels to drop.

While the cow can manage to adapt to this change by increasing calcium absorption from the gut and bone reserves, this may not suffice.

There are various factors which affect a cow’s ability to regulate blood calcium.

This includes age, how much and what it eats, magnesium intake, and whether there are any problems with digestion.

In the latter case, problems such as acidosis or diarrhea will greatly reduce the calcium available for absorption.

Essentially, older cows will not be able to mobilise as much calcium from their skeleton as younger cows.

In cases when the oestrogen levels are high, the calcium mobilisation also ends up being significantly inhibited.

Hypocalcaemia tends to appear more in cows that are fed grass, rather than those that are fed conserved fodder, particularly during wetter, wintry periods.

The older the cow is, and the lower its magnesium intake, thus the higher the chances of having it suffer from this condition.

Besides, hypocalcemia is often accompanied by other problems, including hypomagnesemia and hypophosphatemia.

As soon as a cow has calved, its calcium requirements will increase by around 400 percent.

This occurs since it will need to support colostrum production, and during this period dietary calcium will need to be given.

Milk fever also greatly increases the risk of various other metabolic diseases.

These include metritis and ketosis.

Unfortunately, about 5% of downer cows do not manage to recover.

What are the Symptoms of Milk Fever?

Image source: Pixabay

As noted earlier, the main signs of milk fever are characterised by a lack of muscle function.

In the beginning, it is normal for cows to start walking somewhat stiffly.

Some cows end up throwing their legs to the side in an attempt to retain their balance.

Eventually most cows who are suffering from milk fever will end up becoming downer cows.

They often sit quietly and are unable to rise.

Their coat feels cold and the temperature will be lower than normal.

The cow’s rectum will commonly be full of faeces, and generally the anus will bulge.

Some cows end up developing a fine muscle tremor, and so they can be seen to shiver, particularly over their neck and chest.

If left untreated, the muscle paralysis will end up getting worse.

Eventually the cow will roll over onto its side and not be able to sit back up again.

Due to being in this position, the cow will become bloated.

Sadly, unless proper treatment is provided in a timely manner, such cows generally end up dying.

Thus it is critical to identify signs of milk fever to act as quickly as possible.

It is also worth noting that cows that suffered from either clinical or subclinical hypocalcemia are more likely to be affected again in the future.

Managing & Preventing Milk Fever in Cows

Image source: Shutterstock

Proper management accompanied by preventative measures is always highly recommended.

Indeed, all cases of milk fever can be prevented.

For instance, one should avoid breeding cows or sires which have a history of recurrent milk fever.

It is also important to avoid allowing them to get too fat.

Cows with marked body condition loss are at a much higher risk of suffering from milk fever, according to studies.

Thus, cows need to be given sufficient and proper exercise.

Another key factor is the cow’s diet.

Besides ensuring that the diet allows the cows to have a proper body condition, suitable amounts of magnesium need to be provided.

This is even more important during the late pregnancy stages.

In fact, cows should be supplemented with magnesium both pre and post calving.

The calcium intake during the dry period should be maintained below 50g per day, and whenever possible below 20g.

This will help to improve the efficiency of calcium absorption and its mobilisation.

Then, just before the calving period, this should be increased.

It is also recommended to avoid giving cows feeds that are high in phosphorus.

Some studies also concluded that with diets that are high in sodium and potassium, there could be a higher incidence of cows suffering from milk fever.

It is thus advisable to limit dietary potassium, particularly during the dry and the post-calving period.

A cow that is suspected to be suffering from milk fever needs to be supported and treated properly.

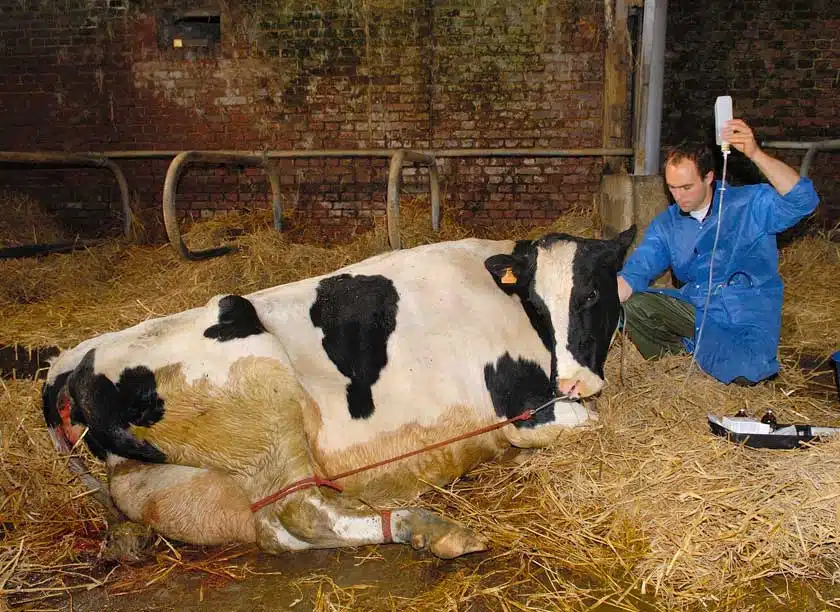

Treating Milk Fever in Cows

Image source: Shutterstock

First of all, it’s important to seek medical assistance so the cow’s condition can be evaluated and diagnosed.

Prior to attempting any form of treatment on a cow, it is recommended to obtain a blood sample.

This can prove to be greatly helpful in the near future, so that in case the cow does not respond as well as expected to the treatment provided, the blood sample will be analysed and one will be better able to assess other treatment methods.

The most common treatment for milk fever is the slow and intravenous infusion of calcium borogluconate.

8 to 14g are generally given as soon as the onset of clinical signs occurs.

In the UK and Ireland, products that contain calcium borogluconate, often with magnesium and phosphorus added to them, are preferred.

The solution should be warmed to be similar to the cow’s body temperature to maximise absorption.

Around 85% of cows respond well after one treatment.

In most cases, cows who were recumbent as a result of milk fever manage to rise within a few minutes of being administered this treatment, while others manage to rise a couple of hours later.

Intravenous therapy with the goal of increasing the cow’s calcium levels quickly is considered to be of great importance to avoid the downer cow syndrome.

It is also important to mention that the success of such treatment will also depend greatly on the careful nursing of the cow.

The cow should then be propped up, kept sitting in a sternal recumbency position and as warm as possible.

Then the cow should be turned carefully to have it lying on the side which is opposite to the one on which it was originally found.

This turning process is best carried out every couple of hours.

It is also important to ensure that the cow is properly sheltered, and that it is kept warm and fed.

The cow’s legs should be massaged from time to time.

In cases when there is no positive response within six hours, the diagnosis will need to be re-evaluated.

Another intravenous infusion of calcium may be administered.

Relapses of milk fever tend to occur in a quarter of cases.

The calcium which is administered will have been eliminated from the cow’s body after twelve hours.

Thus, cases of relapse which occur at intervals of between 18 and 24 hours are often treated in the same way.

In severe cases, it may be considered necessary to remove the calf.

It is also considered wise to screen the blood calcium levels of cows that have recently calved.

Conclusion

Both clinical and subclinical hypocalcemia often leads to a myriad of other problems in cows.

Some of these include slow or difficult calvings, retained placenta, ketosis, mastitis, uterine infections, and fatty liver syndrome.

Over time cows may also end up with a reduced milk yield as well as secondary injuries sustained on the bones, muscles or nerves.

As with any other disease or medical condition for cows, it is important to be careful and always seek medical assistance from a veterinary surgeon.

Nowadays it is also possible to improve management of cattle and their general wellbeing thanks to the emergence of agritech devices, such as the various Moocall calving products one can invest in.

The Moocall calving sensor in particular, is ideal as it can monitor pregnant cows, and alerts you when a cow is about to calve.

The device will not be able to tell if the cow might be suffering from milk fever.

However, calf mortality is significantly decreased if calf deliveries experience fewer complications.

Once the calf is born, you’ll then be in a much better position to assess its health immediately after being born.