Who was Alphonse Mucha?

Alphonse Mucha, born Alfons Maria Mucha, was a renowned Czech painter, illustrator, and graphic artist who resided in Paris during the Art Nouveau era. He gained international recognition for his unique and ornamental theatrical posters, particularly those featuring the actress Sarah Bernhardt. Mucha's artistic talent extended beyond posters, encompassing illustrations, advertisements, and decorative panels, many of which have become iconic representations of the Art Nouveau movement.

In the latter part of his career, at the age of 57, Mucha returned to his homeland and embarked on a monumental project known as The Slav Epic. This series consisted of twenty grand-scale canvases that depicted the history of all the Slavic peoples across the globe. Between 1912 and 1926, he devoted himself to creating these epic works. In 1928, on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of Czechoslovakia's independence, Mucha proudly presented The Slav Epic to the Czech nation, considering it to be his most significant and meaningful body of work.

Alfons Maria Mucha, Self-Portrait, 1899; oil on panel, 32 x 21 cm.

Alfons Maria Mucha, Self-Portrait, 1899; oil on panel, 32 x 21 cm.

Early period

Alphonse Mucha was born on 24 July 1860 in Ivančice, a small town in southern Moravia, which was part of the Austrian Empire at the time (now a region in the Czech Republic). Coming from a humble background, his father worked as a court usher, and his mother was the daughter of a miller. Mucha was the eldest of six children, all of whom had names beginning with the letter "A." His siblings included Anna and Anděla.

From an early age, Mucha displayed a talent for drawing. Impressed by his skills, a local merchant provided him with paper, although it was considered a luxury. During his preschool years, he exclusively drew with his left hand. He also had a musical aptitude and could sing as an alto and play the violin.

Upon completing Volksschule (elementary school), Mucha desired to continue his studies, but his family couldn't afford to support him financially as they were already funding the education of his three step-siblings. His music teacher arranged for him to meet Pavel Křížkovský, the choirmaster of St. Thomas's Abbey in Brno, with the hope that Mucha could join the choir and have his studies sponsored by the monastery. While Křížkovský was impressed by Mucha's talent, he was unable to admit and finance him as he had recently admitted another promising young musician, Leoš Janáček.

Křížkovský then directed Mucha to a choirmaster at the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul, where he was admitted as a chorister and had his studies at the gymnasium in Brno funded. He received his secondary education at the gymnasium and, after his voice changed, he relinquished his position as a chorister but continued to play the violin during masses.

During this time, Mucha developed a deep religious devotion, remarking later, "For me, the notions of painting, going to church, and music are so closely knit that often I cannot decide whether I like church for its music, or music for its place in the mystery which it accompanies." He grew up amidst fervent Czech nationalism across all artistic realms, from music to literature and painting, and actively participated by designing flyers and posters for patriotic gatherings.

While his vocal abilities allowed him to pursue his musical education at the Gymnázium Brno in Brno, the capital of Moravia, Mucha's true passion lay in becoming an artist. He found some employment creating theatrical scenery and other decorations. In 1878, he applied to the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague but was rejected and advised to pursue a different career. Undeterred, at the age of 19 in 1880, he journeyed to Vienna, the political and cultural hub of the Empire, where he secured an apprenticeship as a scenery painter for a theater set production company. During his time in Vienna, he explored museums, churches, palaces, and particularly theaters, for which he received complimentary tickets from his employer. It was in Vienna that he discovered the influential academic painter Hans Makart, renowned for his grand-scale portraits, historical paintings, and murals adorning palaces and government buildings. Makart's style heavily influenced Mucha and steered him towards that artistic direction. Additionally, Mucha began experimenting with photography, a medium that would play a significant role in his future works.

Unfortunately, in 1881, disaster struck when a devastating fire ravaged the Ringtheater, the primary client of Mucha's employer. Left with scarce funds, Mucha embarked on a train journey as far north as his limited resources would permit. He arrived in Mikulov, a town in southern Moravia, and began creating portraits, decorative art, and inscriptions for tombstones. His talent was recognized, and he received a request from Count Eduard Khuen Belasi, a local landlord and nobleman, to paint a series of murals for his residence at Emmahof Castle. Later, he was commissioned to paint murals for Belasi's ancestral home, Gandegg Castle, located in the Tyrol region. Unfortunately, the murals at Emmahof Castle were destroyed by a fire in 1948, but smaller versions of his early work still exist and are currently displayed at the museum in Brno. He demonstrated his expertise in depicting mythological themes, the female figure, and intricate vegetal designs. Belasi, who was also an amateur painter, accompanied Mucha on trips to Venice, Florence, and Milan to explore art and introduced him to various artists, including the renowned Bavarian romantic painter, Wilhelm Kray, who resided in Munich.

Mucha's advertising poster for the Bières de la Meuse.

Mucha's advertising poster for the Bières de la Meuse.

The Munich years

Count Belasi, recognizing Alphonse Mucha's potential, arranged for him to receive formal artistic training in Munich. Belasi generously covered Mucha's tuition fees and living expenses at the prestigious Munich Academy of Fine Arts, and Mucha relocated to Munich in September 1885. Curiously, there is no documented evidence of his enrollment as a student at the academy, raising questions about his actual study there. Nevertheless, during his time in Munich, Mucha formed friendships with notable Slavic artists, including Karel Vítězslav Mašek and Ludek Marold from the Czech Republic, as well as Leonid Pasternak, a Russian artist and father of the renowned poet and novelist Boris Pasternak. Mucha actively participated in the artistic community and established a Czech students' club. He also contributed political illustrations to nationalist publications in Prague. In 1886, he received a significant commission to paint a depiction of the Czech patron saints Cyril and Methodius for a group of Czech emigrants, including some of his own relatives, who had established a Roman Catholic church in Pisek, North Dakota. Mucha found great contentment in Munich's artistic atmosphere, expressing his joy in letters to friends, stating, "Here I am in my new element, painting. I navigate various currents effortlessly and even with delight. For the first time, I am able to achieve the goals that once seemed unattainable." However, the restrictive measures imposed by Bavarian authorities on foreign students and residents forced Mucha to consider other options. Count Belasi proposed that he travel to either Rome or Paris. Supported by Belasi's financial backing, Mucha made the decision in 1887 to relocate to Paris.

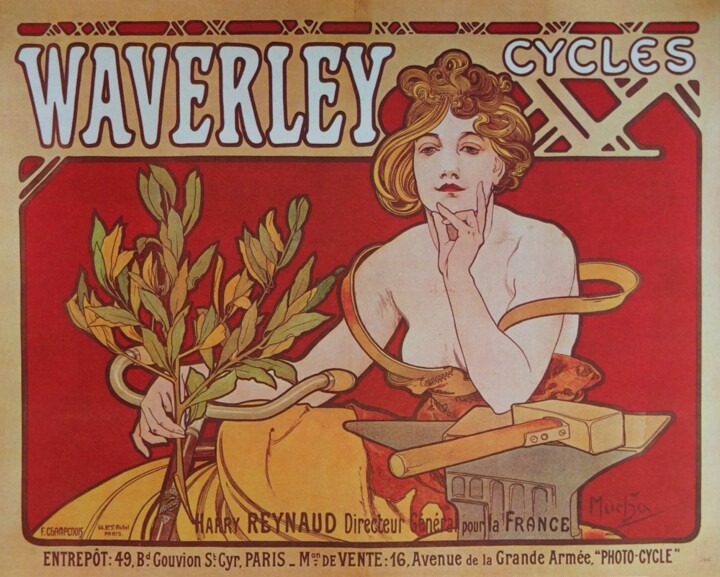

Alphonse Mucha, Waverley Cycles (1898).

Alphonse Mucha, Waverley Cycles (1898).

Paris

In 1888, Alphonse Mucha made the significant move to Paris, where he enrolled in two renowned art schools: the Académie Julian and, the following year, the Académie Colarossi. These institutions offered instruction in a wide range of artistic styles. At the Académie Julian, Mucha studied under Jules Lefebvre, a master of female nudes and allegorical paintings, as well as Jean-Paul Laurens, known for his realistic and dramatic historical and religious works. However, as Mucha neared the age of thirty in 1889, his patron, Count Belasi, deemed that his education had been sufficient and discontinued his financial support.

Upon his arrival in Paris, Mucha found support within the thriving Slavic community. He took up residence in a boarding house called the Crémerie, located at 13 rue de la Grande Chaumière. The establishment, run by Charlotte Caron, was renowned for providing refuge to struggling artists. Caron often accepted paintings or drawings in lieu of rent. Inspired by the success of fellow Czech painter Ludek Marold, who had established himself as an illustrator for magazines, Mucha decided to pursue a similar path. In 1890 and 1891, he began creating illustrations for the weekly magazine La Vie populaire, which serialized novels. Notably, his illustration for Guy de Maupassant's novel, "The Useless Beauty," graced the cover of the May 22, 1890 edition. Additionally, Mucha contributed illustrations to Le Petit Français Illustré, a publication featuring stories for young readers in both magazine and book formats. For this magazine, he produced dramatic scenes depicting battles and historical events, including a cover illustration portraying a moment from the Franco-Prussian War, featured in the January 23, 1892 edition.

His illustrations became a reliable source of income. With his earnings, he purchased a harmonium to pursue his musical interests and acquired his first camera, which utilized glass-plate negatives. He took photographs of himself and his friends, often incorporating them into his drawings. During this time, he formed a friendship with the renowned artist Paul Gauguin and even shared a studio with him upon Gauguin's return from Tahiti in the summer of 1893. Later that year, Mucha also became friends with the playwright August Strindberg, with whom he shared an interest in philosophy and mysticism.

As Mucha's reputation grew, his magazine illustrations transitioned into book illustrations. He received a commission to provide illustrations for Charles Seignobos' book, "Scenes and Episodes of German History," and four of his illustrations, including one depicting the death of Frederick Barbarossa, were chosen for display at the 1894 Paris Salon of Artists. This recognition earned Mucha a medal of honor, his first official accolade.

In the early 1890s, Mucha secured another important client: the Central Library of Fine Arts, specializing in the publication of books on art, architecture, and decorative arts. Additionally, in 1897, the library launched a new magazine called Art et Decoration, which played a crucial role in promoting the Art Nouveau style. Mucha continued to produce illustrations for various clients, including a children's book of poetry by Eugène Manuel, as well as illustrations for a theater arts magazine called La Costume au théâtre.

Alfons Mucha, Portrait of Jaroslava (ca. 1927-1935); oil on canvas, 73 × 60 cm.

Alfons Mucha, Portrait of Jaroslava (ca. 1927-1935); oil on canvas, 73 × 60 cm.

Sarah Bernhardt

At the close of 1894, Alphonse Mucha's artistic career took an unexpected and transformative turn when he began working for the renowned French stage actress, Sarah Bernhardt. The fortuitous encounter occurred on December 26th when Bernhardt placed a phone call to Maurice de Brunhoff, the manager of the publishing firm Lemercier, responsible for printing her theatrical posters. Bernhardt requested a new poster to promote the extension of the play "Gismonda," written by Victorien Sardou, which had already enjoyed significant success since its opening on October 31st, 1894, at the Théâtre de la Renaissance on Boulevard Saint-Martin. Bernhardt insisted that the poster be ready by January 1st, 1895, following the Christmas break. Unfortunately, due to the holiday season, none of Lemercier's regular artists were available.

Coincidentally, Mucha happened to be at the publishing house at that moment, attending to proof corrections. He had previous experience painting Bernhardt, having created a series of illustrations depicting her portrayal of Cleopatra for "Costume au Théâtre" in 1890. In October 1894, when "Gismonda" premiered, Mucha had also been commissioned by the magazine "Le Gaulois" to produce a series of illustrations capturing Bernhardt in the role for a special Christmas supplement, priced at a premium of fifty centimes per copy.

In this situation, Brunhoff approached Mucha and requested him to quickly design the new poster for Bernhardt. The resulting poster exceeded life-size, measuring slightly over two meters in height. It featured Bernhardt dressed as a Byzantine noblewoman, adorned with an orchid headdress and a floral stole, holding a palm branch as part of the Easter procession portrayed in the play's finale. Notably, the poster showcased an innovative element: an ornate, rainbow-shaped arch positioned behind Bernhardt's head, resembling a halo, drawing attention to her face. This distinctive feature would become a recurring motif in Mucha's subsequent theater posters. Due to time constraints, certain areas of the background were left unadorned, without Mucha's customary embellishments. The sole decorative element in the background consisted of Byzantine mosaic tiles positioned behind Bernhardt's head. The poster displayed meticulous draftsmanship and delicate pastel colors, deviating from the vibrant hues commonly seen in posters of that era. The top of the poster, featuring the title, exhibited rich composition and ornamentation, while the bottom succinctly provided the essential information, solely stating the name of the theater.

The poster made its debut on the streets of Paris on January 1st, 1895, causing an immediate sensation. Bernhardt was delighted with the reaction and promptly ordered four thousand copies of the poster for the years 1895 and 1896, subsequently signing Mucha to a six-year contract for further collaborations. With his posters scattered throughout the city, Mucha found himself rapidly propelled into the limelight.

Following "Gismonda," Bernhardt shifted to a different printer, F. Champenois, who, like Mucha, entered into a six-year contract to exclusively work for Bernhardt. Champenois operated a large printing house on Boulevard Saint Michel, employing three hundred workers and boasting twenty steam presses. In exchange for the rights to publish all of Mucha's works, Champenois granted him a generous monthly salary. With his improved income, Mucha was able to relocate to a spacious three-bedroom apartment with a sizable studio within a historic building located at 6 rue du Val-de-Grâce, originally constructed by François Mansart. Mucha proceeded to design posters for each subsequent play featuring Bernhardt.

Mucha's Gismonda.

Mucha's Gismonda.

Posters

The exceptional triumph of Mucha's Bernhardt posters opened doors for him to receive commissions for advertising posters. He embarked on designing posters for a diverse range of products, including JOB cigarette papers, Ruinart Champagne, Lefèvre-Utile biscuits, Nestlé baby food, Idéal Chocolate, the Beers of the Meuse, Moët-Chandon champagne, Trappestine brandy, and Waverly and Perfect bicycles. Collaborating with Champenois, he introduced a novel concept—a decorative panel that served as a poster without text, purely intended for decorative purposes. These panels were printed in large quantities and offered at an affordable price. The inaugural series, titled "The Seasons," was published in 1896, featuring four distinct women immersed in exquisitely ornamental floral settings, symbolizing each season of the year. In 1897, Mucha crafted an individual decorative panel called "Reverie," depicting a young woman in a floral environment, also published by Champenois. He further designed a calendar featuring a woman's head encircled by zodiac signs, which he subsequently sold the rights to Léon Deschamps, the editor of the art review publication La Plume. Deschamps released it in 1897 to great acclaim. Following "The Seasons" series, Mucha continued to create captivating collections such as "The Flowers," "The Arts" (1898), "The Times of Day" (1899), "Precious Stones" (1900), and "The Moon and the Stars" (1902). Between 1896 and 1904, Mucha designed over one hundred poster layouts for Champenois, available in various formats. These ranged from high-end versions printed on Japanese paper or vellum, to more affordable editions featuring multiple images, as well as calendars and postcards.

Mucha's poster designs predominantly revolved around the depiction of enchanting women within opulent surroundings, often with their hair elegantly intertwined in arabesque forms, filling the entire frame. An example of this can be seen in his poster for the railway line connecting Paris and Monaco-Monte-Carlo (1897). The artwork did not showcase a train or any recognizable scene from Monaco or Monte-Carlo; instead, it presented a captivating young woman lost in reverie, encircled by swirling floral patterns, evoking the imagery of rotating train wheels.

The fame garnered from his posters propelled Mucha into the art world's limelight. He received invitations from Deschamps to exhibit his work in the Salon des Cent exhibition in 1896. In 1897, he was granted a major retrospective at the same gallery, featuring an impressive display of 448 artworks. La Plume magazine dedicated a special edition to his oeuvre, and his exhibition embarked on a tour, captivating audiences in Vienna, Prague, Munich, Brussels, London, and New York, thus establishing his international reputation.

Alphonse Mucha, Lefèvre-Utile Champagne Biscuits (1896).

Alphonse Mucha, Lefèvre-Utile Champagne Biscuits (1896).

Paris Universal Exposition (1900)

The Paris Universal Exposition of 1900, renowned as the inaugural grand display of Art Nouveau, presented Alphonse Mucha with an opportunity to venture into an entirely new direction, delving into large-scale historical paintings that had captivated him during his time in Vienna. This event also offered him a platform to express his Czech patriotism. His foreign-sounding name had aroused considerable speculation in the French press, which greatly troubled him. However, Sarah Bernhardt came to his defense, asserting in La France that Mucha was "a Czech from Moravia not only by birth and origin, but also by sentiment, conviction, and patriotism." Motivated by his desire to showcase his Czech heritage, he applied to the Austrian government and was commissioned to create murals for the Pavilion of Bosnia and Herzegovina at the Exposition. This pavilion showcased the industrial, agricultural, and cultural achievements of these provinces, which, in 1878, had been wrested from Turkish rule and placed under Austrian administration as a result of the Treaty of Berlin. The temporary structure built for the Exposition featured three expansive halls on two levels, with a ceiling towering over twelve meters high, allowing natural light to flood in through skylights. Mucha's experience in theater decoration equipped him with the skills necessary to swiftly paint large-scale artworks.

Initially, Mucha conceived a series of murals depicting the suffering endured by the Slavic inhabitants of the region under foreign occupation. However, the exhibit's sponsors, the Austrian government, as the new authority in the region, deemed this concept too pessimistic for a World's Fair. Consequently, he modified his project to portray a future society in the Balkans where Catholic and Orthodox Christians, along with Muslims, coexisted harmoniously. This revised concept was accepted, and Mucha commenced his work. To ensure authenticity, he embarked on a journey to the Balkans, where he sketched Balkan costumes, ceremonies, and architecture to incorporate into his artwork. His decoration encompassed a significant allegorical painting titled "Bosnia Offers Her Products to the Universal Exposition," alongside an additional set of murals on three walls, illustrating the historical and cultural development of the region. Discreetly, he included some depictions of the Bosnians' sufferings under foreign rule, subtly positioned in the arched band at the top of the mural. Similar to his approach in theater work, Mucha often photographed posed models and then painted from these photographs, simplifying the forms. While his work portrayed dramatic events, the overall impression conveyed was one of serenity and harmony. Additionally, in addition to the murals, Mucha was also responsible for designing the menu for the restaurant housed within the Bosnia Pavilion.

Mucha's artistic contributions took on various forms at the Exposition. He designed posters for the official Austrian participation in the event, crafted menus for both the Bosnian Pavilion's restaurant and the official opening banquet. Moreover, he created displays for jeweler Georges Fouquet and perfume maker Houbigant, featuring statuettes and panels depicting women symbolizing scents such as rose, orange blossom, violet, and buttercup. His more profound artworks, including his drawings for "Le Pater," were showcased in the Austrian Pavilion and the Austrian section of the Grand Palais.

As a result of his contributions to the Exposition, Alphonse Mucha received notable recognition for his work. The Austrian government honored him with the title of Knight of the Order of Franz Joseph, while the French government bestowed upon him the Legion of Honour. During the Exposition, Mucha put forward an unconventional proposal. The French government had initially planned to dismantle the Eiffel Tower, which had been specifically erected for the event, once the Exposition concluded. However, Mucha suggested an alternative idea. He proposed that, following the Exposition, the top of the tower should be replaced with a sculptural monument symbolizing humanity, to be placed upon its pedestal. The Eiffel Tower, capturing the fascination of both tourists and Parisians alike, gained immense popularity, leading to its preservation even after the Exhibition concluded.

Mucha at work on Slavic Epic.

Mucha at work on Slavic Epic.

America

In March 1904, Alphonse Mucha embarked on his first visit to the United States, sailing to New York. His primary objective was to secure funding for his ambitious project, The Slav Epic, which he had conceived during the 1900 Exposition. With letters of introduction from Baroness Salomon de Rothschild, Mucha arrived in New York already celebrated due to the widespread display of his posters during Sarah Bernhardt's American tours since 1896. He rented a studio near Central Park, where he created portraits, gave interviews and lectures, and established connections with Pan-Slavic organizations.

During a Pan-Slavic banquet in New York City, Mucha encountered Charles Richard Crane, a wealthy businessman and ardent Slavophile. Crane commissioned Mucha to paint a portrait of his daughter in a traditional Slavic style. More significantly, Crane shared Mucha's enthusiasm for a series of monumental paintings depicting Slavic history, and he became Mucha's most important patron. Notably, Mucha used his portrait of Crane's daughter as the model for Slavia on the 100 koruna bill when he later designed Czechoslovak banknotes.

In a letter to his family in Moravia, Mucha explained his decision to come to America, stating that he needed to escape the demands and constraints of Paris if he wanted to pursue the projects he truly desired. He emphasized that he sought not wealth, comfort, or personal fame in America, but rather the opportunity to engage in more meaningful work.

Although Mucha had unfinished commissions in France, he returned to Paris in May 1904 to complete them before heading back to New York in early January 1905. Over the next few years, he made four more trips to the United States, staying for extended periods of five to six months each time. In 1906, he returned with his new wife, Marie Chytilová, whom he had married in Prague. Mucha remained in the U.S. until 1909, during which time his primary income came from teaching illustration and design at various institutions. He also undertook a few commercial projects, such as designing boxes and a store display for Savon Mucha, a soap brand, in 1906. Notably, he decorated the interior of the German Theater of New York with three large Art Nouveau-style allegorical murals representing Tragedy, Comedy, and Truth.

Despite his artistic ventures, Mucha's time in America was not entirely successful. His portrait painting skills were not his forte, and the German Theater closed just a year after its opening. While he did create posters for prominent American actresses like Mrs. Leslie Carter and Maude Adams, they often resembled his previous Bernhardt posters. However, one of his notable achievements during this period was his portrait of Josephine Crane Bradley, daughter of his patron, depicted as Slavia in traditional Slavic attire, surrounded by symbols from Slavic folklore and art. Mucha's connection with Charles Richard Crane paved the way for his most ambitious project, The Slav Epic.

Selena Mattei

Selena Mattei