Milk fever (clinical hypocalcaemia) is a common problem in dairy cows estimated to occur in 5-7% of the milking herd.

‘Downer cow‘, milk fever cases are caused by a drop in blood calcium (<5.5 mg/dL) which then affects the cow’s ability to contract her muscles and stand.

What is often not appreciated is the significance of subclinical milk fever (blood calcium 5.5-8.0 mg/dL), when the blood calcium is below normal but not severe enough to cause any signs such as problems walking.

In these cases, the farmer is unaware of a problem, but the issue is still impactful on herd health and profits.

Preventative strategies to address both clinical and subclinical milk fever should be implemented in dairy herds to reduce incidences of post-fresh cow diseases and maximise profits.

What causes milk fever

Calving and the start of a new lactation challenges a cow’s ability to maintain normal blood calcium. Milk is very rich in calcium, and cows must shift bodily functions to adjust to the sudden calcium outflow.

Normal mechanisms to pull calcium from bone storage take 24-48hrs to mobilise in the face of immediate demands for calcium outflow into colostrum.

This puts cows in a deficient state from calving until 24-48hrs post-calving, at which point they can effectively regulate calcium supplies from their bodies.

Cascade of negative health consequences

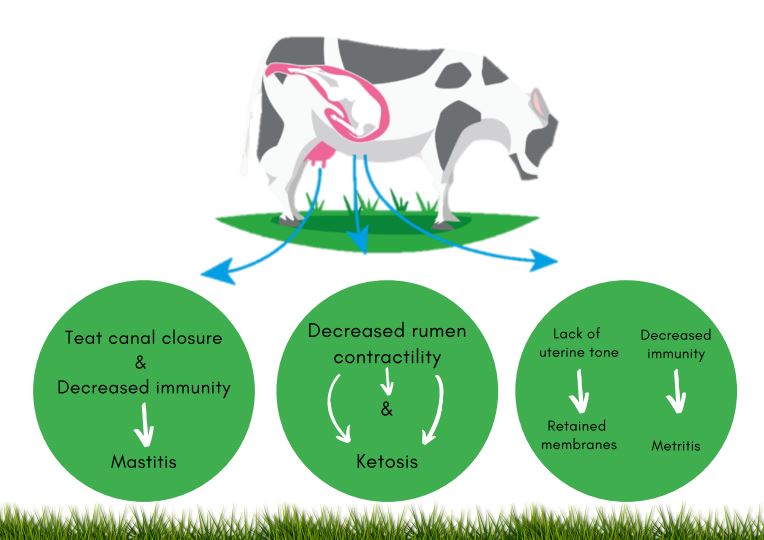

Hypocalcaemia, or blood calcium below normal (<8 mg/dL), has been linked to a variety of problems in fresh cows. This happens because calcium is essential for muscle and nerve function, especially functions that support skeletal muscle strength and gut motility.

Problems in either of these two areas can trigger a cascade of negative events that ultimately reduce feed intake, increase metabolic disease and decrease milk yield (Fig. 1).

Additionally, subclinical milk fever has also shown to impair immunity which can lead to further diseases i.e. mastitis or metritis.

Conditions arising secondary to hypocalcaemia can be costly to farmers not only in management, but with further reduced milk yields and negative fertility consequences.

Economic impact of milk fever

Subclinical milk fever is more costly than clinical milk fever (‘downer cow’) because it affects a much higher percentage of cows in the herd. It is estimated subclinical milk fever, which does not have signs a farmer would recognise, accounts for 80% of the costs of milk fever within a herd.

A European study estimated the prevalence of subclinical milk fever in multiparous cows is 57% and in first-lactation heifers is 16%. Each case of subclinical milk fever is estimated to cost €100 including reduced milk yield and management of subsequent diseases such as ketosis.

Recent work from University College Dublin (UCD) estimates the average cost of clinical milk fever is €312.27. Conservatively, a 100-cow herd with 20 replacement heifers would then be estimated to lose €6,000 due to milk fever annually (Fig. 2).

Practical prevention strategies

Several proactive, preventative strategies can be implemented on dairy farms to manage milk fever. It is recommended to work closely with your vet to develop the optimal strategy for your herd.

Pre-calving diets should be restricted in calcium to help prime the body’s response for calcium regulation. This can be difficult to achieve with background levels of calcium in forage.

A carefully formulated pre-calving diet containing anion salts can be fed to achieve a negative dietary cation-anion difference (DCAD), which promotes a calcium flux. Nutritional and veterinary consultation is again necessary to formulate an appropriate DCAD nutritional plan.

Oral calcium supplementation at the time of calving is an effective and economical approach to preventing clinical and subclinical milk fever. Most commercial oral calcium products last 12 hours, requiring repeat administration to cover the cow through her entire 24–48hr critical period when she is mobilising calcium and at high risk for milk fever.

Calcium boluses allow a targeted approach to cows at higher risk for milk fever.

Risk factors for milk fever include:

- Age: The risk of milk fever increases as much as 9% per lactation;

- Body condition score >3.5;

- Jersey or Guernsey breeds;

- High-yielding cows;

- Lame cows;

- Cows with previous history of milk fever.

Electropidolate Max is the only 40hr calcium and magnesium bolus on the Irish market that will enable a single bolus administration period to cover the entire critical duration of milk fever.

Calcium and magnesium are delivered with pidolate salt, a technology from human medicine that enhances calcium absorption within the gut. This makes the calcium and magnesium more available to the cow and serves as a reliable mineral source to achieve normal blood calcium levels.

Milk fever is an important determinant of fresh cow health and milk production.

The majority of losses due to milk fever are unseen as subclinical cases, and a proactive approach to improve herd health and enhance profits should be applied in Irish dairy herds.

Speak to your vet about how Electropidolate Max boluses can help manage milk fever for your herd.

By Lauren Popiolek, DVM, BSA, Interchem and PharVet veterinary technical advisor

References available upon request.